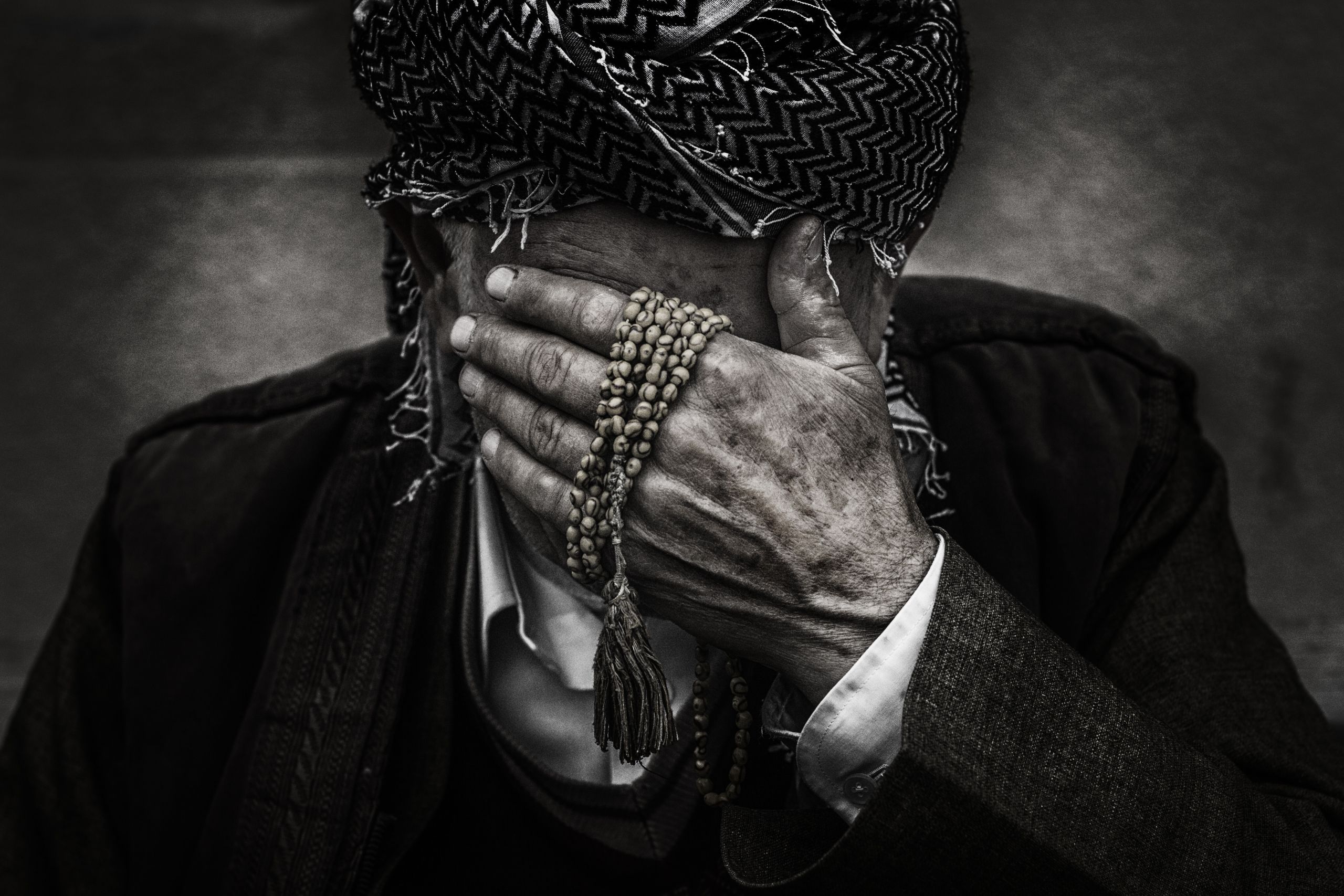

Hannah and Colleen chat about several key terms in Kurdish language and culture: sherma, aiba, and haram. All have meanings that connect to honor, shame, and what is allowable and what is forbidden. Cultural expectations and norms are part of what can be a challenge for a westerner. This podcast explores their shades of meaning and how we perceived them as we lived in the region.

To learn more about our work in Iraq head over to our Iraq page!

Email us at Hannah@servantgroup.org if you have any questions!

Here’s a rough transcript!

Hannah: Hey Colleen.

Colleen: Hey Hannah.

Hannah: So this is “Between Iraq and a Hard Place”. Although it kind of looks like a storage closet.

Colleen: Seriously though, we are here to talk about life in Iraq.

Hannah: Right. We’re gonna go back to some linguistic interesting things.

Colleen: Because not everything is translatable into English or like has the same connotations and meanings even if you have a translation of it.

Hannah: And we talked about this a little bit when we talked about “wasta” which is kind of… it’s still really hard to define but it can means like, you scratch my back I’ll scratch yours. Like the owing of favors.

Colleen: The brownie points system on a large scale.

Hannah: So today we’re going to talk about three words.

Colleen: Which are all related!

Hannah: And all kind of have similar connotations but varying degrees of intensity about them. So we’re going to talk about the words “Aiba”, “Sherma” and “Haram”. Two of those words are Arabic. One of them is Kurdish.

Colleen: But as Kurdistan is part of… at least Iraqi Kurdistan is part of Iraq and it’s in the middle of the Middle East, Arabic vocabulary are really common and often are used interchangeably without an outsider being able to know that, you know, these words come from this language root and these words come from that language root.

Hannah: The only reason that I know that one of these words is Kurdish is that we asked our language consultant, Ringo Star, former student of mine got on Snapchat with her and we’re like hey can you like tell us what this is.

Colleen: Like we have ideas and we know how they got used around us when we lived there or how we were told to use them. But whether or not that is how they’re actually used or thought of in the culture was something we decided we could use a little input on.

Hannah: Because we want to be accurate on our podcast as much as possible. So let’s start with either Aiba.

Colleen: Aiba. I think it’s probably one of the first words I was taught.

Hannah: Really?

Colleen: Yeah, I was taught that if I was ever walking around in the bazaar or somewhere and someone did something inappropriate whether I was touched inappropriately or someone was too close, especially men, that I could shout “Aiba!” at them and then they would go away.

Hannah: And did they tell you what Aiba meant?

Colleen: You know, probably? But for a while I I probably wouldn’t translated it. I would have been like that’s what you yell at someone who’s doing something inappropriate.

Colleen: Right. Like I always thought that it tt was just like shame or shame on y, ou which is kind of how I was told ny Nationals that’s how it’s used. But according to Google Translate it actually means like flaw or blemish. And it is a slightly different pronunciation at least it sounds slightly different than the way that we were taught to use it. It is it does kind of have that connotation of the thing that you are doing is wrong and I’m going to call you out on i

Hannah: t. Yeah. I never really heard that word used in a way that was not excmatoryre. Even if someone was telling a story or you know talking about somebody else’s actions it’s like they were aiba o I just can’t believe they did that it w aibaer. Yeah. So while the definition maybe is not sha, me the cultural meani, ng at least in Kurdist, an is saying that you’re doing it shamefu

Colleen: l. I’m calling out shame on yo

Hannah: u. Ye.

Colleen: Which is st not something we do in the United States in that dire of v e aw. Ly like we will shame people on call out their actions to be wrong but we don’t have a universal term that’s li, ke if I use this set of phrases this is what everybody use

Hannah: s. Right. Like when was the last time you were in the grocery store and you heard someone telling their kids that they’re acting shameful, you’re re misbehaving. Sure. But not like you are bringing shame on the famil h. It is not an American concept for one thing but also not something that we would say to peopl

Colleen: e. It’s just not part of our cultural vocabular

Hannah: y. But that’s definitely how it’s used. And you get an immediate response from whoever you are calling ou

Colleen: t. I fortunately never had to use it in public like that. I did see other people get called out in publi

Hannah: c. I would I would hear teachers use it all the tim

Colleen: Oh . I real?

Hannah: Ly like to shame their students. Or like be standing in a classroom and have a teacher or some of the administration come in and go off on a tear. And I wouldn’t understand anything except for the wo “Aiba”. And ow you’re like oh what they’ve do somethingn

Colleen: They’ve ve done something wro!

Hannah: g. I don’t know what it is that they have done something. A sherma ma is a similar wo, rd like similar meani.

Colleen: Bg but I mean it does literally mean sha, right?e.

Hannah: Right.

Colleen: Instead of meaning like a flaw. And even though it’s used in the same way, someone can call out someone and say, “Sherma!”. It can be used that way I guess intrinsically doesn’t have any tie to a specific flaw or blemish or fault right.

Hannah: Yeah. So sherma is Kurdish right as opposed to Aiba being Arabic and I feel like I heard sherma my used much more jokingly. You know two kids in class that are giving each other a hard time about something and one of them would be like it’s almost like a, Ooo you did a bad thing! kind of context.

Colleen: It’s funny that you say that because while I don’t think I could have pulled that out as like an example it does feel less serious to me it does feel less strong and intense.

Hannah: Right. Most the context I heard it in was a teasing sort of, oh you’re going to bring shame to your family. Mm. Oooh girl! And I would do that to my students sometimes, too because they knew that like I wasn’t shaming them I would just be like, “Tch sherma!” But you have to get that “tch” at the front.

Colleen: Because that also it’s like a whole word in itself. It’s shame all by itself. Right. Look at the little click.

Hannah: If you’re walking through a store and you hear like especially an older Kurdish lady be like “tch” then you know like it’s 20 times louder than that.

Colleen: Right. I don’t know how to make it as loud as they do.

Hannah: No, we’d have to get Mary in here for that she’s good at it.

Colleen: But it’s funny because that is one of those things that I feel like I did pick up for a while. I think I’ve lost it now. But when someone even cuts you off in traffic or you know like it’s just that “tch”.

Hannah: Yeah, which is like immediate shame on them.

Colleen: It’s subtle but also weirdly not subtle. I don’t know how to explain that.

Hannah: Right. You hear that noise like my immediate response now is like, What have I done wrong? You know how you have that thing that there’s like a look on your mom’s face and you’re like, Oh no I’m in such trouble like that sound does it for me.

Hannah: Yeah.

Hannah: I’m just like, I’ve done something terribly wrong!

Colleen: Even though most of the time it was not directed at me. There’s far too much grace for the foreigner for most foreigners to get called out for being shameful or you know sherma, aiba or the click. They’re far too kind to us to call us out for things like that.

Hannah: Both of those words, sherma and aiba, kind of speak to that collective cultural shame thing that is really foreign and really hard to understand as an American. The things that I do are not only a reflection on me and who I am but upon my community be that the wider, all Americans are like this, community or all of the teachers at the school are like this community or my roommates that I’m with or even just the foreign community within the Kurdish community.

Colleen: In the United States we’re so individualistic that even if someone’s family members are behaving badly we even use the phrase like the black sheep of the family.

Hannah: Right.

Colleen: As like they’re separate and they’re doing their own thing and that has no reflection on the rest of the family’s value or standing in society. Whereas their that black sheep, as we would say, is what’s going to define that entire family. Like that is, Oh, the brother, like he is not an outlier. They must all be that way and they just hide it well.

Hannah: Right. That whole guilt by association thing is real. That if the people you hang out with or God forbid the people you’re related to do something bad or wrong or even just kind of weird or culturally abnormal your whole family is labeled with that. It’s hard to convey that. I had a hard time getting new people to understand that concept that like, your behavior reflects on me. Your reputation is also my reputation and my reputation is also your reputation. If I have a good reputation within the school and then you come along living with me working with me you get loaned my good reputation. It’s great; it’s wonderful. It will cover you for a little while but then if you are like mean or lazy or whatever, that’s then going to reflect on me. Like it’s my fault that you’re acting that way which is kind of a stressful way to live when you constantly have complete strangers that you are now like sharing your reputation with.

Colleen: But to some extent you can’t control who you’re sharing because like you said sometimes it’s the entire expat you know international community that you are now sharing your reputation with and that you know has its good sides and its bad sides. I think we did manage at least with some people to have groupings. You know, we were teachers not oil contractors. So you know we didn’t necessarily carry the shame of the dudes who came in and drank a lot and partied at the clubs all weekend. You know some of that carryover is like, oh you’re Americans. Of course you must all be that way. But you’re right you can’t control it and that can make it stressful.

Hannah: Right. And you can’t there. You’re right to that there is some ability to make a distinction between like me and everyone else. I think one of the things that was a struggle is that because Kurds do all kind of know each other…

Colleen: They’re all related.

Hannah: They’re all related or they all know who’s related to who. They don’t have a concept of how big and diverse the U.S. is. And so they figure you know especially if someone is living with you, you guys must have known each other for a while.

Colleen: Yeah.

Hannah: Or be related in some way. And so there came a point where I just had to start explaining I don’t know this person, really like they’re living with me.

Colleen: I’m getting to know them…

Hannah: But I’m getting to know them, I don’t know them super well. Sorry. I can’t help you; I don’t have wasta with them. Almost.

Colleen: Yeah. And they don’t understand wasta in the first place. So like this is just how we’re going to have to deal.

Hannah: Yeah. So I think you can get to a point where you’re like, you can teach you your closer circles like, there are distinctions between believers and the rest of Americans. Like not all Americans are Christian, for one thing. But even within that scope not all of those Christians are actual followers of Jesus. It’s just Christian in the sense of that’s the religion they would identify with.

Colleen: There’s a lot of those kind of groups and categories and things where we have to define our tribe the way they don’t have to think about or define their tribes because their tribes are all familial or they’ve got these established groups. And so helping them define our tribe with us. But again you can’t get away from some sort of group identity and the shame that you bring or acquire from that group identity there. There are no true isolated individuals, which can be frustrating I know, it has been frustrating to a lot of our American staff, but at the same time I think is somewhat reflective of truth in that we can’t live independently. We are part of a community. We do have responsibilities to that community. And what we do matters in that community.

Hannah: Yeah, I think the biggest example that I saw of that in my time in Kurdistan was a Kurdish person in a different city who had committed a great crime against the American community and happened to be the American community that was also part of my community. So different city, different context, and having my neighbors in my city, my Kurdish neighbors, come over to my house after they found out about this thing and apologize to me that this thing had happened.

Colleen: Yeah.

Hannah: And not just like, Oh I’m so sorry for you. It was I am so ashamed that someone that was Kurdish would do a thing like this. Like weeping and tears because they felt that collective guilt of like, Please don’t think all Kurdish people act this way, please don’t.

Colleen: But even more than that. Like a sense of weirdly responsibility for this crime that in America we would never think that they had any responsibility for.

Hannah: Right.

Colleen: But they had this this feeling of responsibility for the fact that someone from their tribe, their people had done this.

Hannah: Yeah. I I just I thank those my second year there and I was just really taken aback by the strength of their guilt over it. And to be able to sit down and have that conversation of, We forgive you for this. Like in the back of my mind it was like you didn’t do anything wrong. But obviously you feel really guilty. So let me try to help you work through this. I think that was the first time that I was ever like, oh this is for real.

Colleen: This is how far it goes.

Hannah: I just wanted to interrupt myself. I mean I came to ask you to do us a favor. Share this podcast with someone that you think could find it interesting or amusing and let them know about Servant Group International. We’re always looking for more people who are crazy like us and want to go to Iraq. And so if you know someone who fits that bill, share this podcast with them. Pause, while you have time, share this podcast. Thanks so much. And now back to me.

Hannah: The other word.

Colleen: There is one more word!

Hannah: There is one more word and that word is haram which maybe you’re familiar with. Haram has much more of a almost religious sort of tinge to it.

Colleen: Yeah I mean that’s the only time I really saw it used was when certain things were religiously forbidden.

Hannah: And that’s what that means it means to forbid, also an Arabic word. So yeah it has much more of the religious connotation of this is a sin if you do it.

Colleen: It was applied to things like dogs and pork and alcohol and…

Hannah: …smoking.

Colleen: Hahah! I don’t know that I ever heard it applied to smoking.

Hannah: It’s just ignored.

Colleen: But yeah it was like these are the things that especially as Muslims we do not do that they are forbidden things.

Hannah: So it’s super serious word never, I never heard it used in a joking context.

Colleen: And I almost never heard it in a like a yelled out or social context really at all. I only ever really heard it when there was some sort of conversation about what was right or wrong.

Hannah: And this is where I think that the nuance is that like Aiba or Sherma is like this is a shameful thing but not necessarily wrong, like you shouldn’t do it. But if you don’t get caught then it’s not a big deal. Where Haram is like you do not do that even if you don’t ever get caught. The thing that you are doing is a sin. It is wrong. It is always wrong in all contexts.

Colleen: Yeah. Which is funny to me in the sense that I would have conversations with someone and they would say, Oh yeah. As a Muslim alcohol is haram but that didn’t necessarily mean that they didn’t drink alcohol but they knew it was the forbidden thing. They knew they weren’t supposed to. And you’re right. It didn’t matter whether they did it in secret. It wasn’t going to stop being haram if it were secret.

Hannah: Where other things like you know if you cheat on a test that’s sherma, shameful. But if you can get away with it like, meh!

Colleen: Obviously you were smart enough to get that grade and so you deserve it.

Hannah: But if you go out and have sausages for dinner and you know that it’s sausage and it’s got pork in it that’s haram. You are going to be held accountable for that. Whether you eat them in your living room in the dark or you know in the middle of a restaurant. And again I think that’s a tricky concept in some ways. Like, we’re so used to having moral gray areas or like even the idea as as Christians that like yeah I can commit a sin but it’s going to be forgiven or it has already been forgiven. I feel like a haram is almost almost like an unforgivable thing. Not always. Because there are things that you can do as a Muslim to..

Colleen: To like outweight it. I mean the concept of forgiveness doesn’t work the same way.

Hannah: I don’t think I was ever told that something was haram for me. Because as a Christian it’s not haram.

Colleen: According to your rules you can do anything you want!

Hannah: Do whatever you want to. Right. You are free is what I always heard. Oh you’re a Christian, you are free. You don’t have to cover your hair. You don’t have to, you know, whatever the case may be. Definitely much more of a moral concept as opposed to like a social one.

Colleen: Right. Whereas as Christians I feel like I was raised with much more of a like a universal moral aspect to things like there’s not this social shame that comes from most things. Something is not wrong because it can cause you or your family shame. There might still be shame for things like you know not having nice clothes or something but you’re like that’s not a moral category. But like all of the other things are wrong because they are morally wrong not because you could get caught. Like that cheating on a test is morally wrong because it’s a lie not because you got caught.

Hannah: It’s interesting to tease those things out with with Kurds.

Colleen: Because they’ve, just the same way Americans don’t think about those categories deeply until you encounter something or someone that’s different. They also have never thought about categorizing those things differently.

Hannah: And it’s interesting to see people come against things like cheating, especially American teachers to come up against those and be like, No this is wrong. And in our minds haram wrong. Like this is a forbidden thing that you do not do.

Colleen: Right.

Hannah: Where in their minds it’s sherma wrong. It’s wrong if I get caught and when you don’t have those terms defined well for an American teacher to come in and say like this is wrong wrong not just shameful wrong the shameful wrong thinkers are gonna be like, What are you talking about?

Colleen: That’s not like eating pork or drinking alcohol, right? How dare you put that in the same category.

Hannah: This is not a forbidden thing. And so it can feel like you’re banging your head against a wall to be like. No, but it’s wrong, but it’s not wrong, but it is, but it’s not wrong. I’ve seen so many people get frustrated by that.

Colleen: I’m sure. I mean I was frustrated over it at first. Like trying to figure out what on earth was going on with this. And you know over time and talking it through with people and figuring out eventually I figured it out. Did that make me stop clamping down on students who cheated. No. But I knew how to phrase it in a way that made sense to them right. No, I am not going to accept your cheating. It is wrong for you because for your benefit you need to understand and know this information not just for a score but because what I am teaching you is actually valuable for you. And by cheating you are missing out on the value that is the point of this class. Did that entirely stop cheating? No. Because some people don’t believe you when you tell them you’re doing something for their good. But for a lot of them it made sense.

Hannah: Right. And there are other cultural pressures going on around joining like it’s not a single issue issue. It’s multifaceted. And I think that’s what we now try to train people is it’s how you talk about the thing that you see as wrong which is you know from a Christian moral standpoint. Cheating is wrong because it is lying and lying is bad. But how you talk about that and how you can contextualize for that, that for them in a way that they will understand because you’re not coming from the same thought place. We tried to teach people how to do that. But there is inevitably something that comes along that is like, Oh well, this is wrong. And I know that this is wrong but I don’t know how to explain to you that I know that it is wrong in a way that like you’re going to understand why it’s wrong.

Colleen: It’s good to be a learner. Ask lots of questions and not assume that the things you think of as universal are actually culturally, religiously universal.

Hannah: Right. Especially in a lot of ways. My Muslim friends are some of the most moral people that I know, in a lot of ways. But that doesn’t it’s a different… like that morality is coming from a different place than where my morality maybe is coming from. So it’s really easy to forget that like, oh we don’t see things exactly the same, from exactly the same perspective. Like our actions may make it seem like we do, but we don’t. And I think that’s where it ultimately comes down to is like we have Aiba, Sherma, and Haram. And those words mean very different things culturally in Kurdistan than they would for similar words in the US. It’s one of those things that like you don’t think about; you don’t go into a culture assuming that like even the very words that you use are going to be construed differently, understood differently. And it can be really disorienting. But it’s also kind of fun.

Colleen: Yeah! It’s one of the most interesting things that I remember thinking through were different terms and cultural understandings and ideas because they also give you a lens into your own culture and your own life and things that you took for granted that are maybe unusual or weird compared to what’s in other cultures.

Hannah: We talk about that a lot more in the culture shock episodes. And this this is kind of another aspect of culture shock is the way that wrongs and rights are dealt with that can seem unjust or unfair to us but always have some kind of cultural root and background.

Colleen: And at some point we’ll do an episode on “honor” .

Hannah: Right. The flip side!

Colleen: The flip side of that because it has its own characteristics and challenges and…

Hannah: …morals. Like morals for honor and…

Colleen: Oh and how you show honor to someone.

Hannah: So we’ll get around to that. It’s going to be a big one.

Colleen: Think about your own sense of community and how your community affects your behavior.

Hannah: Yeah. Whether that be your family, your work community, your school community…

Colleen: …maybe church community.

Hannah: … maybe even your church community how do all of those different spheres influence you and how you behave and how you see the world. And let us know!

Colleen: You can find us at Servant Group International on Facebook or Instagram or on our website at hannah@servantgroup.org.

Hannah: Yeah, and if you have a question that we haven’t answered yet send us an email or Facebook message. We’d love to hear from you! Thanks for listening!

Hannah: … or because you’re dumb and you don’t know how to answer the questions.

Colleen: Right.

Hannah: Yeah……… yeah.